The water does not look like a battlefield. On a calm day, the South China Sea shimmers under a tropical sun, an immense expanse of cerulean blue stretching from the Chinese mainland to the shores of Borneo. To the uninitiated eye, it is a vision of tranquility, its surface broken only by the silhouettes of fishing junks, the slow march of container ships, and the occasional spout of a migrating whale. Yet, beneath this placid surface, a titanic struggle churns. This body of water, bordered by more than half a dozen nations and home to a dizzying array of tiny, contested islands, shoals, and reefs, has become the 21st century’s most complex and perilous geopolitical chessboard.

This is not a war of trenches and thunderous artillery, at least not yet. It is a slow, grinding conflict fought with coast guard cutters, maritime militias disguised as fishing fleets, competing maps, and the relentless dredging of sand to build military outposts on once-submerged coral. It is a battle of narratives, where ancient history collides with international law, and national pride clashes with the cold, hard logic of global economics.

The South China Sea is more than a mere territorial dispute over specks of land. It is a crucible where the defining forces of our era are being tested. It is here that an ascendant China, seeking to reclaim what it sees as its historical sphere of influence, directly challenges the post-World War II, American-led global order. It is here that the fundamental principles of international law, particularly the freedom of navigation and the sanctity of exclusive economic zones, face their most potent threat. And it is here that smaller nations must perform a terrifying diplomatic tightrope act, balancing their sovereign rights against the overwhelming economic and military gravity of their colossal neighbor.

To understand the South China Sea is to understand the tectonic shifts reordering our world. It is a masterclass in modern statecraft, revealing how geography, history, resources, and ambition intertwine to create a flashpoint with the potential to destabilize the entire globe. This case study will dissect this intricate conflict, peeling back the layers of history, untangling the motivations of the key players, weighing the immense stakes, and exploring the potential futures that ripple out from this contested saltwater frontier.

The Tyranny of Geography and the Weight of History

Geopolitics begins, always, with the map. The physical reality of a place dictates its strategic value, its vulnerabilities, and its potential. As the political geographer Nicholas Spykman famously asserted, “Geography is the most fundamental factor in foreign policy because it is the most permanent.” In the South China Sea, geography is not just a factor; it is destiny.

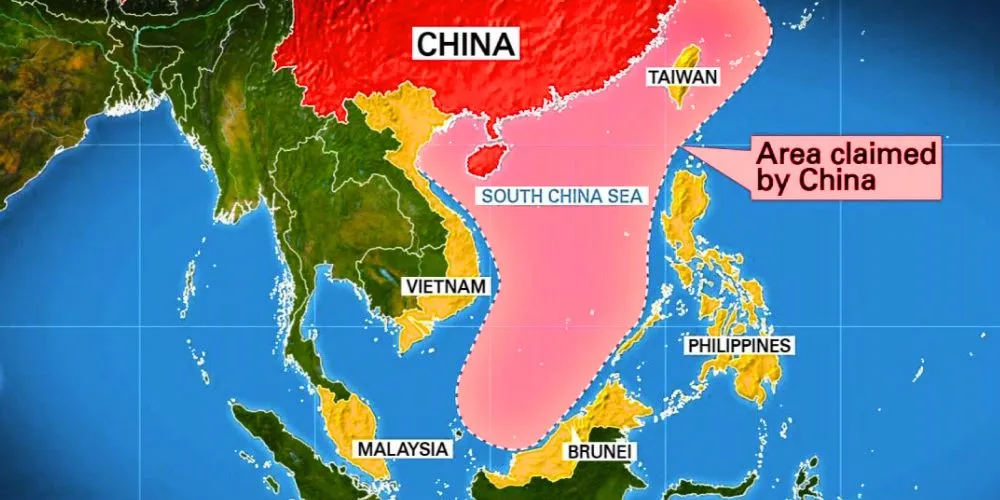

The sea itself is a vast, semi-enclosed basin, covering some 3.5 million square kilometers. It acts as a critical throat connecting the Pacific and Indian Oceans. To the east, it is bounded by the Philippines and Taiwan. To the west, by Vietnam and the Malay Peninsula. To the north, by the southern coast of China. To the south, by Borneo, Indonesia, and Singapore. This geography creates a natural maritime superhighway. The Strait of Malacca, a narrow chokepoint between Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra, funnels a staggering portion of global trade into the southern end of the sea. Over one-third of all global shipping, carrying an estimated $5.3 trillion in trade annually, transits these waters. For nations like China, Japan, and South Korea, it is an economic lifeline. Over 80% of China’s crude oil imports pass through this very corridor. Control the South China Sea, and you hold a potential stranglehold on the economies of Northeast Asia.

Theorists of sea power like Alfred Thayer Mahan would immediately recognize the strategic imperative. Mahan argued that national greatness was inextricably linked to control of the seas, which guaranteed commercial access and the ability to project military power. From this perspective, the South China Sea is not just a body of water; it is a grand strategic prize. A nation that dominates this sea can secure its trade routes while threatening those of its rivals. It can project power deep into Southeast Asia and out into the wider Pacific.

But the sea’s value extends beneath its surface. Scattered across its expanse are hundreds of small, mostly uninhabitable features, clustered into two main archipelagos: the Paracel Islands in the north and the much larger Spratly Islands in the south. For centuries, these were little more than hazards to navigation, occasional shelters for fishermen caught in storms. Today, they are the conflict’s epicenters. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), even a tiny, naturally formed island can generate a 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), granting its owner sovereign rights over any resources found in the water column and on the seabed. The region is believed to hold significant, though not fully proven, reserves of oil and natural gas, along with some of the world’s most productive—and increasingly overexploited—fishing grounds. In an age of resource scarcity, these rocks and reefs have transformed into keys to immense potential wealth.

This potent geography is layered with an even more complex and contested history. The narrative each nation tells about its past forms the bedrock of its present-day claims. For China, the story is one of ancient dominion. Chinese maps and texts dating back centuries refer to the sea and its islands, which Beijing asserts prove its irrefutable historical sovereignty. This narrative is deeply intertwined with the concept of the “Century of Humiliation,” the period from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century when a weak China suffered invasions and unequal treaties at the hands of Western powers and Japan. Reasserting control over the South China Sea is, therefore, not merely a strategic calculation; it is a core component of President Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream” of national rejuvenation—a symbolic righting of historical wrongs.

This narrative found its most concrete expression on a map. In 1947, the then-ruling Republic of China (ROC) government drew a U-shaped, eleven-dash line around the vast majority of the South China Sea, claiming everything within it as Chinese territory. When the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established in 1949, it adopted this map, later removing two dashes in the Gulf of Tonkin to create the infamous “Nine-Dash Line.” This line, deliberately ambiguous and lacking precise coordinates, slices deep into the legally recognized maritime zones of Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia. It is a claim based not on international law, but on a selective interpretation of history.

Other nations, however, have their histories. Vietnam points to its ancient texts and evidence of its administration over the Paracels and Spratlys for centuries. It recalls a long and bloody history of resisting Chinese domination, a fierce nationalistic spirit that informs its refusal to cede ground today. The Philippines bases its claims on proximity and discovery, particularly regarding the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal, which lie well within its EEZ. For these and other Southeast Asian nations, China’s historical narrative is not one of benign oversight but of imperial ambition, a story they have resisted for generations.

The post-World War II era added another layer of complexity. The 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, which formally ended the war with Japan, saw Japan renounce its claim to the islands it had occupied. Critically, however, the treaty failed to specify to whom the islands should be returned, leaving a power vacuum that the various claimants rushed to fill. In the decades that followed, a “creeping occupation” began, with China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Taiwan all placing troops and building rudimentary structures on the tiny features they could physically control. The sea became a patchwork of competing flags, a low-level standoff waiting for a catalyst. That catalyst arrived with China’s dramatic economic and military rise at the turn of the century.

The Grand Chessboard and Its Players

The South China Sea conflict is a drama with a large cast, but three principal actors dominate the stage: China, the United States, and the collection of Southeast Asian claimant states, known as ASEAN. Each player operates with a distinct set of motivations, strategies, and constraints, creating a dynamic and volatile strategic triangle.

The Ascendant Dragon: China’s Calculus of Power

For Beijing, the South China Sea is not a peripheral issue; it is central to its grand strategy for the 21st century. Its motivations are a potent blend of nationalism, security, and economics.

First and foremost is the imperative of sovereignty and national pride. The Communist Party of China derives a significant portion of its domestic legitimacy from its promise to restore China to its rightful place as a global power and to wash away the shame of the Century of Humiliation. The Nine-Dash Line is a non-negotiable symbol of this restoration. To cede any part of it would be seen as a sign of weakness, an unacceptable concession that would undermine the Party’s authority.

Second is strategic security. Chinese military strategists are acutely aware of the “Malacca Dilemma”—their nation’s over-reliance on the narrow strait for its energy and trade. They are also fixated on the “First Island Chain,” a concept denoting the string of archipelagos from Japan through Taiwan and the Philippines to Borneo, which they view as a barrier erected by the United States and its allies to contain China’s naval power. By controlling and militarizing the islands within the South China Sea, China aims to achieve several objectives simultaneously. It can protect its vital sea lanes of communication (SLOCs), create a strategic buffer for its southern coast and its nuclear submarine bastion on Hainan Island, and establish forward-basing capabilities that allow its navy to “break out” of the First Island Chain and project power into the Western Pacific.

To achieve these goals, China has employed a masterful and patient strategy, operating primarily in the “gray zone”—the murky space between routine statecraft and open warfare. Its most visible tactic has been the “Great Wall of Sand.” Starting around 2013, China embarked on an unprecedented island-building campaign, using massive fleets of dredgers to suck up sand from the seabed and deposit it onto submerged reefs in the Spratlys, such as Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef. It transformed these features into large, artificial islands, complete with deep-water ports, military-grade airfields, radar arrays, and missile emplacements. In a few short years, it had created a network of unsinkable aircraft carriers in the heart of the South China Sea, fundamentally altering the strategic landscape in its favor.

Complementing this is the “cabbage strategy.” This involves surrounding a contested feature with concentric layers of vessels. At the core might be a People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) warship, kept over the horizon. Closer in are the white-hulled ships of the increasingly muscular China Coast Guard. The outermost layer consists of the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM), a vast fleet of what appear to be ordinary fishing trawlers but are state-organized, state-paid assets trained to harass, intimidate, and swarm the vessels of other nations. This strategy allows Beijing to assert control and bully its neighbors into submission without firing a shot, creating plausible deniability and forcing other nations to either escalate to a military confrontation or back down.

The Anxious Hegemon: America’s Balancing Act

The United States, geographically distant, has no territorial claims in the South China Sea. Yet, it views the conflict as a direct challenge to its role as the principal guarantor of the global commons and the architect of the post-war international order. Its primary stated interest is the preservation of freedom of navigation and overflight (FON). As the world’s leading maritime power, the U.S. insists that the sea lanes of the South China Sea must remain open to all nations for lawful commerce and transit, as enshrined in UNCLOS. China’s expansive claims and its tendency to demand permission for foreign military vessels to pass through what the U.S. considers international waters represent a fundamental threat to this principle. If China can successfully close off or control this vital artery, it could set a precedent for other strategic waterways around the world.

Beyond this principle lies the crucial role of alliances and credibility. The U.S. has mutual defense treaties with several nations in the region, including the Philippines and Japan. Its credibility as an ally rests on its willingness and ability to stand by these partners in the face of coercion. If Washington is seen as unable or unwilling to push back against Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, its security guarantees worldwide would be devalued, potentially leading allies to bandwagon with China or pursue their nuclear deterrents, sparking regional arms races. The conflict is, therefore, a test of American resolve.

America’s primary tool for pushing back is its military presence. It conducts regular Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs), where U.S. Navy warships deliberately sail within 12 nautical miles of China’s artificial islands to challenge Beijing’s claims to a territorial sea around them. These operations are carefully choreographed legal and military statements, designed to demonstrate that Washington does not recognize China’s claims. Furthermore, the U.S. has been strengthening its regional alliances. It revitalized the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the “Quad”) with Japan, Australia, and India. It formed the AUKUS security pact with the United Kingdom and Australia, all with the implicit goal of balancing Chinese power. It has also increased military aid, training, and joint exercises with claimant states like the Philippines and Vietnam.

However, the U.S. faces significant constraints. The geographic reality of “the tyranny of distance” means that China is fighting in its backyard, while the U.S. must project power from thousands of miles away. There is also a constant fear of miscalculation. A collision between a U.S. and a Chinese vessel, or a tense aerial encounter, could rapidly escalate into a full-blown military conflict between two nuclear-armed powers—a catastrophe that both sides desperately wish to avoid.

The Squeezed Middle: The ASEAN Claimants

Caught between these two giants are the Southeast Asian nations, particularly the claimants: Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei. (Indonesia, while not a claimant to the islands, has seen its Natuna Sea EEZ encroached upon by the Nine-Dash Line.) These nations are in an extraordinarily difficult position. On the one hand, China’s actions represent a direct threat to their sovereignty, their national resources, and their dignity. On the other hand, China is their largest trading partner, a vital source of investment, and an inescapable, permanent neighbor.

This duality forces them into a complex hedging strategy. They cannot afford to confront China fully, nor can they afford to capitulate completely. Their responses have varied, often dictated by domestic politics and their risk tolerance.

Vietnam has been the most consistently assertive of the claimants. Fueled by a deep-seated historical suspicion of Chinese expansionism and a powerful sense of nationalism, Hanoi has quietly but steadily upgraded its military capabilities, acquiring submarines and advanced missiles to create a credible deterrent. It has also been one of the most vocal critics of Chinese actions within ASEAN and has actively courted closer security ties with the U.S., Japan, and India.

The Philippines presents a more volatile case study. Under President Benigno Aquino III, Manila took the bold step of taking China to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. But his successor, Rodrigo Duterte, dramatically reversed course, dismissing the subsequent legal victory, cozying up to Beijing in exchange for promised investments, and railing against the U.S. Yet, under the current administration of Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the pendulum has swung back again, with Manila reasserting its claims, strengthening its alliance with Washington, and granting U.S. forces access to more military bases. This whiplash demonstrates the profound impact that domestic leadership can have on a nation’s geopolitical posture.

Malaysia and Brunei, with their own significant offshore energy interests, have typically pursued a quieter diplomacy, preferring to handle disputes behind closed doors to avoid jeopardizing their strong economic ties with Beijing. Yet, they have been forced to become more assertive as Chinese coast guard and militia vessels have become more aggressive in harassing their oil and gas exploration activities.

The collective body of ASEAN has struggled to form a united front. The organization operates on the principle of consensus, which China has expertly exploited by leveraging its influence over members like Cambodia and Laos to block any strong, unified statements critical of its actions. The long-running negotiations for a legally binding Code of Conduct (CoC) in the South China Sea have stalled for years, largely because China insists that any agreement must first recognize its “indisputable sovereignty”—a non-starter for the other claimants.

The Cores of Contention – Rules, Resources, and Routes

The conflict in the South China Sea revolves around three fundamental and interlocking issues: the rules that govern the seas, the resources that lie beneath them, and the routes that pass over them.

The Law of the Sea versus the Law of Power

At the heart of the dispute is a clash between two irreconcilable worldviews. One is based on the modern, rules-based international order, epitomized by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). UNCLOS, which has been ratified by over 160 countries (including China and all the Southeast Asian claimants, but notably not the U.S., though it accepts its provisions as customary international law), provides a comprehensive legal framework for the world’s oceans. It defines territorial waters, contiguous zones, and, most importantly, the 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Within its EEZ, a coastal state has the exclusive right to explore and exploit natural resources. The convention makes it clear that historical claims, unless continuously and explicitly maintained and recognized, do not supersede these legally defined zones. Furthermore, it states that features that are submerged at high tide, known as low-tide elevations, cannot generate any maritime zones of their own.

The other worldview is the one advanced by China, based on its claim of “historic rights” encapsulated by the Nine-Dash Line. Beijing argues that its sovereignty over the sea predates UNCLOS by millennia and therefore cannot be constrained by it. This is a direct challenge to the very foundation of the modern legal order.

This clash came to a head in 2013 when the Philippines, under President Aquino, initiated arbitration proceedings against China under UNCLOS. Manila did not ask the tribunal to rule on the sovereignty of the islands themselves—something the court lacked jurisdiction to do—but rather to clarify the legality of China’s actions and the status of the maritime features. In July 2016, the arbitral tribunal in The Hague delivered a sweeping and unambiguous ruling. It found that there was no legal basis for China’s claim to historic rights within the Nine-Dash Line. It ruled that China’s island-building on low-tide elevations was illegal and that its actions had violated the Philippines’ sovereign rights within its EEZ. It was a stunning legal victory for the Philippines and a powerful affirmation of the rules-based order.

China’s reaction was one of fury and defiance. It had refused to participate in the proceedings from the start, and it declared the ruling “null and void” and “a piece of waste paper.” The state-run media launched a propaganda blitz, painting the tribunal as a Western plot to contain China. By flatly rejecting the ruling, China sent a clear and chilling message: when international law conflicts with what it perceives as its core national interests, it will choose its interests. This act has profound implications. It signals a move toward a more multipolar world where power, not law, may become the final arbiter of disputes, a world that looks more like the 19th century than the 21st.

The Bounty of the Sea: Black Gold and Blue Harvests

While the legal and strategic battles rage, the conflict is also driven by the raw, tangible value of the sea’s resources. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates that the region contains approximately 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in proven and probable reserves. While not on the scale of the Persian Gulf, these are significant prizes for the energy-hungry economies of the region, particularly China, which is the world’s largest oil importer. Securing domestic sources of energy is a matter of national security, reducing reliance on volatile global markets and vulnerable supply lines. This explains the intensity of the standoffs that regularly occur when Malaysian or Vietnamese survey ships attempt to explore for hydrocarbons in their EEZs, only to be met by intimidating Chinese coast guard vessels.

Equally important are the fisheries. The South China Sea accounts for over 12% of the global fish catch, providing a critical source of protein and livelihoods for millions of people in coastal communities. However, this vital resource is in a state of crisis due to overfishing, destructive practices like dynamite and cyanide fishing, and the immense environmental damage caused by China’s island-building, which has destroyed thousands of acres of pristine coral reefs—the breeding grounds for fish stocks. The competition for dwindling fish stocks is a constant source of friction. Filipino and Vietnamese fishing boats are routinely rammed, harassed, and have their catches confiscated by Chinese maritime forces, turning fishermen into frontline soldiers in a battle for survival.

The Global Economic Jugular: The SLOCs

Ultimately, the most significant stake for the wider world is the security of the sea lanes. The South China Sea is not just a regional waterway; it is a global economic jugular. The vast majority of manufactured goods from Asia’s workshops, the energy supplies for its industrial powerhouses, and the raw materials that feed them all pass through this channel.

A military conflict that disrupts or closes these sea lanes, even for a short period, would have catastrophic consequences for the global economy. Shipping insurance rates would skyrocket. Supply chains, already shown to be fragile during the COVID-19 pandemic, would snap. The flow of everything from semiconductors to sneakers would halt, triggering inflation, factory shutdowns, and economic recession across the globe. This is why nations with no direct claims, such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, India, and European powers like the UK, France, and Germany, have all taken a keen interest in the dispute. They understand that the principle of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea is not an abstract concept; it is a prerequisite for their economic prosperity and security. The battle for the South China Sea is, in a very real sense, a battle for the future of globalization itself.

Navigating the Future – Scenarios and Consequences

The currents of the South China Sea are pulling the region and the world toward an uncertain future. The complex interplay of forces allows for several potential scenarios, ranging from a continued, simmering standoff to a catastrophic great-power war.

The Enduring Gray Zone (The Most Likely)

The most probable future, at least in the short to medium term, is a continuation and intensification of the status quo. In this scenario, China continues to leverage its gray-zone tactics: the steady presence of its coast guard and militia, the harassment of other claimants’ economic activities, and the slow normalization of its military presence on the artificial islands. It will avoid actions that would cross a clear red line and trigger a military response from the United States, such as seizing a feature currently occupied by another country or declaring an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the sea.

For the U.S. and its allies, this presents a frustrating “death by a thousand cuts.” They will continue to respond with FONOPs, joint military exercises, and diplomatic condemnations. ASEAN nations will continue their hedging, protesting Chinese actions while trying to maintain economic ties. This scenario avoids open war but comes at a steep price. It slowly erodes international law, as China’s de facto control becomes a fait accompli. It normalizes coercion as a tool of statecraft. And it keeps the entire region on a permanent knife-edge, where the risk of the second scenario is ever-present.

The Spark and the Inferno – Accidental Escalation

This is the nightmare scenario that keeps strategists in Washington and Beijing awake at night. In the crowded and contested waters and airspace of the South China Sea, the potential for a miscalculation is dangerously high—a collision between two warships playing a high-stakes game of chicken. A trigger-happy Coast Guard commander rammed a fishing vessel too hard, causing fatalities. An aggressive maneuver by a fighter pilot leading to a mid-air collision, as almost happened in 2001 with the Hainan Island incident.

In such a crisis, nationalism and public pressure on both sides could quickly overwhelm the rational calculations of leaders. A localized incident could spiral out of control through a rapid, tit-for-tat escalation. The U.S. might feel compelled to respond militarily to uphold its credibility, and China might feel it cannot back down without suffering a national humiliation. A direct military conflict between the United States and China, even one confined to the South China Sea, would be an economic and human catastrophe on a scale not seen in generations. It would instantly halt global trade, shatter the world economy, and carry the horrifying risk of escalating to the nuclear level. While both sides are aware of this danger and have established some military-to-military hotlines, the intense distrust and heightened operational tempo make this a terrifyingly plausible outcome.

The Diplomatic Long Game – A Faint Hope for a Code of Conduct

The most optimistic, and perhaps least likely, scenario involves a genuine diplomatic breakthrough. For over two decades, ASEAN and China have been negotiating a Code of Conduct (CoC) to manage disputes in the sea. In theory, a legally binding and enforceable CoC could establish rules of the road, create de-escalation mechanisms, and provide a framework for joint resource development.

However, the obstacles remain immense. The fundamental disagreement over the Nine-Dash Line and sovereignty has yet to be bridged. China has consistently sought a CoC that would exclude “outside powers” (i.e., the United States) from military activities in the region and would require its consent for any joint energy exploration between a claimant state and a foreign company—terms the other claimants see as a back-door way of legitimizing Chinese control. ASEAN’s internal divisions also make it difficult to negotiate with a single, powerful voice. A meaningful CoC remains a distant aspiration, a faint glimmer of hope in a sea of strategic competition.

Conclusion: A Sea of Reflection

The South China Sea is far more than a collection of rocks, reefs, and contested coordinates on a map. It is a mirror reflecting the anxieties and ambitions of our age. It reflects the raw power of geography to shape the destinies of nations. It reflects the enduring weight of history, both real and imagined, in fueling modern conflict.

What is unfolding in these tropical waters is the most significant test of the international order in the 21st century. It pits two fundamentally different visions of the world against each other. One vision, championed by the United States and its allies, is of a world governed by a common set of rules and laws, where disputes are resolved through peaceful arbitration and the global commons are open to all. The other vision, advanced by China, is of a world where historical claims and the prerogatives of great powers can override international law, a return to a sphere-of-influence model of geopolitics.

The outcome of this struggle is far from certain. The Dragon has built its fortresses of sand, entrenching its physical presence with each passing day. The Hegemon sails its powerful fleets, asserting its legal rights in a show of resolve. The smaller nations caught in between navigate the treacherous tides, seeking to preserve their sovereignty without being crushed by the giants.

The ripples from this sea will not be contained. They will wash over the global economy, shape the future of international law, and define the balance of power for decades to come. The quiet shimmer on the surface of the South China Sea belies the turbulence beneath. It is a deceptively calm frontier where the future of the global order is being written, one defiant patrol, one dredged ton of sand, and one tense standoff at a time. The world watches, holding its breath, hoping the waves do not break into a tsunami.